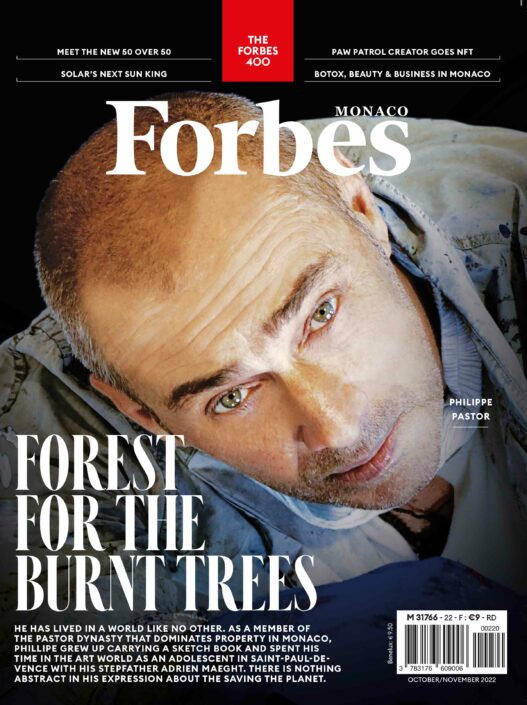

Forest for the Burnt Trees

He has lived in a world like no other. As a member of the Pastor dynasty that dominates property in Monaco, Phillipe grew up carrying a sketch book and spent his time in the art world as an adolescent in Saint-Paul-De-Vence with his stepfather Adrien Maeght. There is nothing abstract in his expression about the saving the planet.

By Lanie Goodman

His deep gravelly voice might have belonged to a rock singer; his tone, sober and emphatic. And if he had his way, says Philippe Pastor, he would line France’s highways with replanted blackened Trees charred by fire.

Widely known for his series of 7-meter-high sculptures, “Burnt Trees,” recently on exhibit in front of the Monte Carlo Casino for the 73rd Monegasque Red Cross Gala last July, the Monegasque artist is unequivocal about his intent—inspiring vigilance and reminding people of one of many environmental perils that endanger the future of our planet.

“Man is self-destructive,” the 61-year-old declares, and goes on to explain the origin of his tree sculptures, which date back to 2003. While working in his former atelier in La Garde Freinet, a wooded hilltop town near Saint Tropez, Pastor was trapped in a devastating forest fire that raged for several days. During the aftermath, surrounded by ashes and smoke, the artist hauled several carbonized tree trunks to his workshop, lined them up, and decided to combine them with debris taken from crashed cars.

“I added painted scraps of sheet metal from cars that had been totaled in accidents to accentuate that self-destructive aspect,” explains Pastor. For the works recently installed at the entrance to Saint-Paul-de-Vence at the Saint Roch round-about, his choice of primary colors is a sly tribute to Matisse, Calder and Miró. These monumental installations are scattered across the globe—Paris’ Gare du Nord, Nice’s airport, the United Nations in Nairobi, as well as in Milan, New York and Singapore.

With ateliers in Monaco and Spain (“I spend six months in each place”), various honors including the Knight of Order of Cultural Merit, awarded by Prince Albert, and international recognition for his series of powerful gigantic abstract paintings, Pastor’s career is anything but typical.

First, he is self-taught, and methodic in his approach. Take, for example, his series “Avec le Temps,” where the artist combines a celestial blue made from natural pigment from the Atlas Mountains with natural materials. “I use leaves, pine needles, bits of wood —not flowers since they turn to dust after a few months—and combine them with different kinds of glue. Before you can talk about the esthetic of a painting, there is a lot of time and research that goes into finalizing a canvas—first, second and third layers of paint, drying it either with a fan or in the sun, allowing it to weather outside, and the different tools I use in the process. For my monochrome paintings, I’ve spent the last fifteen years reflecting on the problematic of the lack of water on earth, which includes pollution of the oceans and the scarcity of drinking water.”

Similarly, Pastor’s series on glaciers brings him to the climatic disasters of the North Pole. “I was very interested by the dominance of white, black and the slightest hint of sky blue that you see in the ice,” he enthuses.

So how exactly did Pastor enter the world of art? “I’ve always carried around a sketch book. And I used to try to copy Braque and Calder when I was young,” he says, evoking, in passing, his time spent in the art world as an adolescent in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. And above all, his immense admiration for his stepfather, Adrien Maeght, art dealer and collector, whom his mother remarried when Pastor was fourteen. “Obviously, I spent time at the Fondation Maeght and knew a lot of artists like César,” Pastor says, frowning, “but I’d rather not dwell on those anecdotes today.”

[…]